Arbitrary U.S. Tariffs Are Gone. What's Next?

The Supreme Court has ruled that the President cannot use "emergency" authority to impose tariffs at will. Inflation is still going to be a problem.

“Who pays the tariffs?” has been a surprisingly contentious question over the past year or so.

Back in April, Steve Miran, who was then in charge of the Council of Economic Advisers, had argued that foreigners would bear the cost as their currencies depreciated. (Equivalently, the U.S. dollar would appreciate if investors decided that making things in America had become relatively more attractive.) Alternatively, foreign producers could cut their selling prices to preserve their market share. Either way, Americans would not have paid higher prices as a result of the tariffs.

That is not what happened. Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York recently observed that foreign producers have barely cut their prices when selling to Americans, while the dollar has depreciated over the past year. Most of the extra customs duties have therefore been paid by U.S. importers, although the exact split between manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers is still ambiguous. Everyone else who has bothered to look has found the same thing. Yet, Kevin Hassett, who is best known for writing Dow 36,000 and for predicting that the Covid pandemic would only last a few months because of a “cubic model”, said the NY Fed paper was “the worst paper I’ve ever seen in the history of the Federal Reserve system”.

I have previously argued that the entire debate misses the point. Tariffs are just taxes. If Americans “pay” the tariffs directly they will have lower incomes, which could lead to less spending on goods and services, including those produced in the rest of the world. If foreigners “pay” by lowering their prices, they will have lower incomes, which could also lead to less spending on goods and services, including those produced by Americans.

Regardless of who “pays”, what matters is that the U.S. government is taking away spending power from some combination of the U.S. private sector and the rest of the world. The ultimate impact depends on the extent to which Americans, the foreign private sector, and foreign governments are willing to dissave in response to this U.S. fiscal tightening.

Thankfully, it turns out that the question is largely moot because the answer is that nobody is paying the tariffs. The Supreme Court has finally stated the obvious: using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to arbitrarily impose import taxes is illegal.

The ruling does not affect the sectoral tariffs that have been and may be imposed under Section 201 of the 1974 Trade Act, the sectoral tariffs that have been and may be imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, nor does it affect the country-specific tariffs that have been and may be imposed under Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act. But the Supreme Court ruling does wipe out the tariffs that were capriciously imposed over concerns about fentanyl as well as the “liberation day” tariffs that were devised by a chatbot. There will likely be refunds.

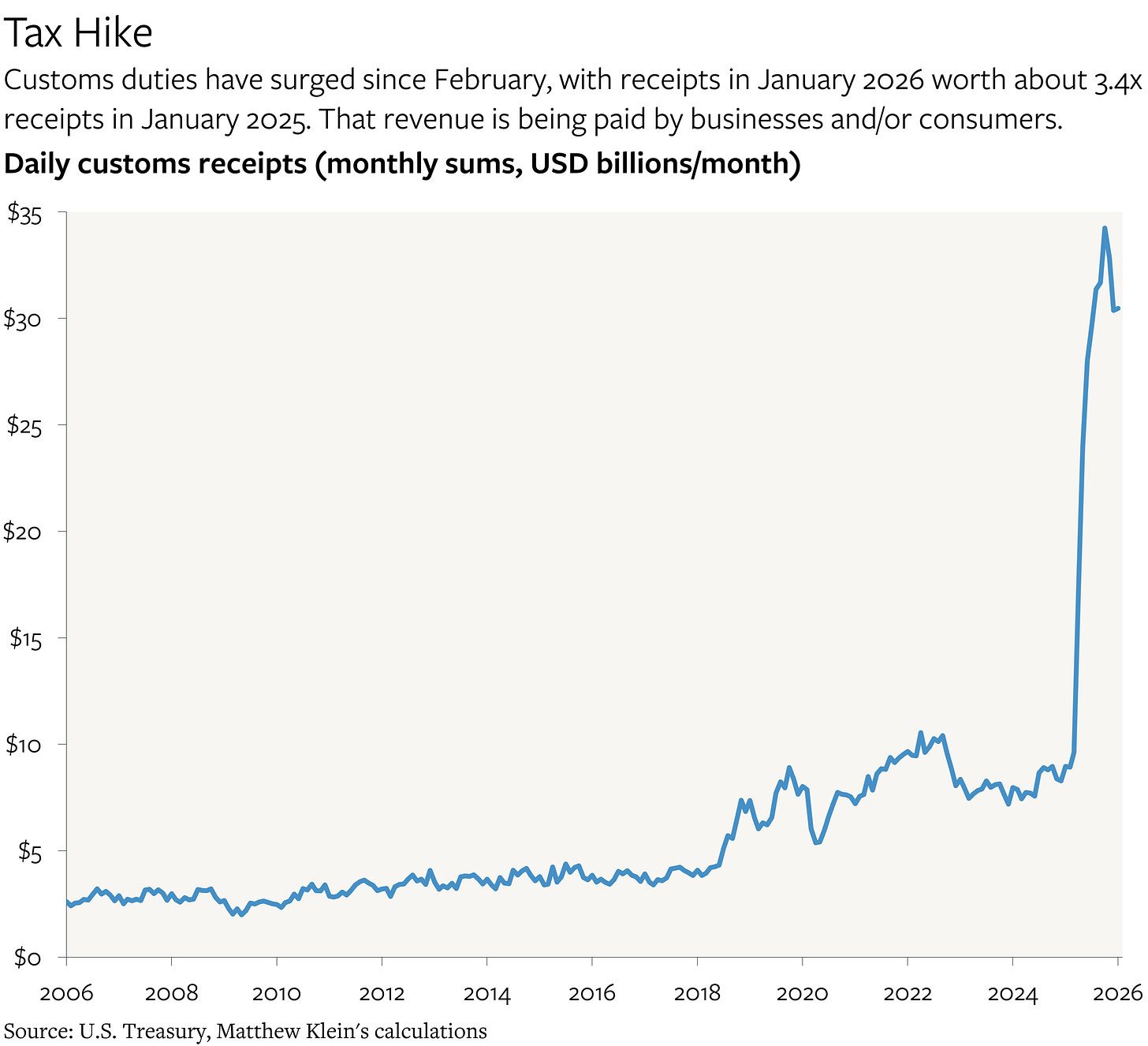

According to Customs and Border Patrol, as of mid-December 2025, the Treasury had collected about $133.5 billion in tariffs attributable to IEEPA, plus $49 billion in Section 232 sectoral tariffs, and about $41 billion in Section 301 China tariffs.

The administration has announced that it will use its authority under Section 122 of the 1974 Trade Act to impose worldwide tariffs of 10%1 to compensate for the loss of IEEPA. This measure is limited by law to “a period not exceeding 150 days”. According to the Yale Budget Lab, this should more or less restore the average effective tariff rate after losing IEEPA, although the net impact on revenues would still be negative given the time limit and the refunds.

Is it theoretically possible that many of the tariffs that were just removed could be recreated within the next five months using legal means? Maybe. But it would require heroic levels of effort by the technocrats who remain at the Commerce Department and the office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), assuming they even want to do it.2 It would also be hard to raise whatever tariffs were imposed at the conclusion of any investigations without starting the process over again. The administration has therefore lost much of its ability to arbitrarily raise taxes and threaten perceived enemies, which should be particularly relevant for Brazilians and Europeans.3

That is just as well, because the tariffs of the past year clearly failed on their own terms, except insofar as they raised taxes by about 1% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) without the consent of Congress.

According to the latest figures, price-adjusted spending on imports rose by more than real U.S. export earnings, with the net result subtracting 0.2 percentage points from the 2025 growth rate. Despite tariffs, Americans did not switch from buying foreign-made goods to domestic goods, nor did the tariffs suppress U.S. demand for imports relative to foreign demand for U.S. exports. Excluding gold, which is not counted in the GDP numbers, the trade deficit in 2025 was $921 billion, or 3.0% of GDP, essentially unchanged from 2024. These numbers include the surge in imports in the beginning of 2025 in anticipation of tariffs, but that does not change the overall picture.

More importantly, after accounting for the rebound in Boeing’s production of airplanes, which remains below where it was in 2018, U.S. industrial production has been more or less stagnant over the past year. Business investment was decent, but that was only thanks to the boom in data center construction—and that mostly means spending on foreign-made semiconductors and networking equipment, which were exempted from tariffs.

So at least some of the farce is over. What is the macro impact?