Chinese Weakness is the Real "China Shock"

It has been over a year-and-half since the end of "Covid Zero" restrictions, but domestic demand is still so weak that production is only holding up thanks to exports (dumping?)

The Chinese government’s management of the economic consequences of the pandemic was uniquely bad. Its policy errors compounded longstanding structural issues in the distribution of income, harming not just the Chinese people, but workers in the rest of the world.

The latest data confirm that the economic imbalances flagged by Chinese officials as early as 2007 are only getting worse, with Chinese producers increasingly reliant on dumping excess output into world markets as a partial offset to the damage caused by the depressed consumer market. Many top Chinese economists—in think tanks, academia, the private sector, and retired officials—now believe that the government must respond by directly lifting household spending power. The question is whether this will happen, and if so, by enough. (The Wall Street Journal reports that Xi Jinping remains opposed on ideological grounds.) If not, China’s internal imbalances could once again wreak havoc on producers elsewhere—unless they take effective countermeasures.

China’s Undershoot

The Chinese economy in 2024 is about 5% smaller than what economists at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had expected it would be in their October 2019 forecasts. None of the other major economies have a shortfall nearly as large.1 Meanwhile, China’s trade and current account surpluses have been multiples of what the IMF had originally projected.

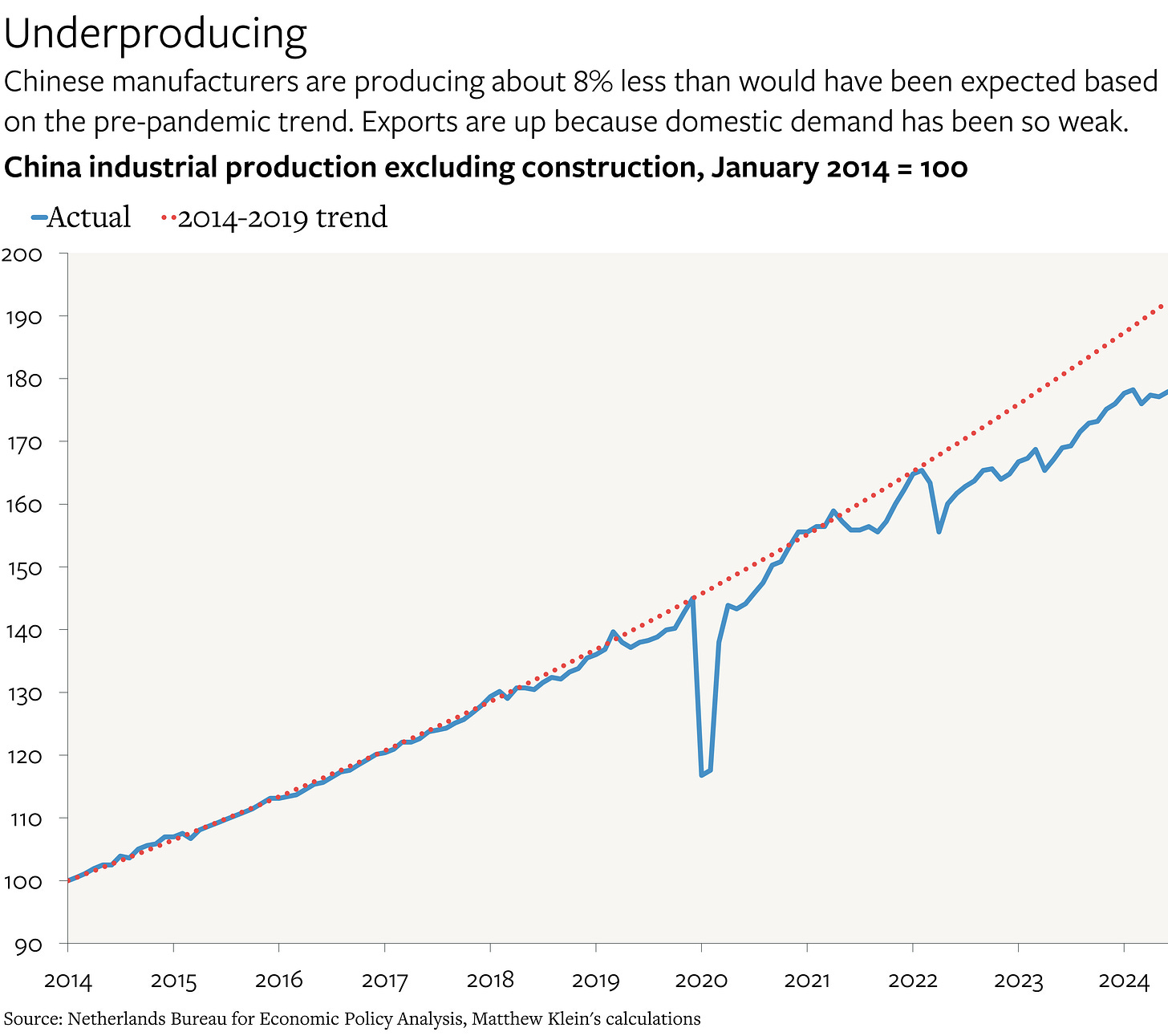

These forecast errors are connected. China’s industrial output has grown by about 23% since December 2019—substantially less than would have been expected based on the pre-pandemic trend—but its real export volumes are up by about 34% even as its real imports have only increased by 6% over the past five years.

China’s recent emergence as a major net exporter of motor vehicles has not coincided with a production boom—total assemblies are no higher the peak in 2018—but with weak domestic sales.

The weakness in Chinese demand is concentrated among households. Nominal retail spending on consumer goods and meals has grown at an average rate of just 3.5% a year since 2019. That is not just an artifact of the pandemic. Nominal spending in January-July 2024 was just 3.5% higher than in January-July 2023. The current pace of retail spending is about 16% below what might have been expected based on the pre-pandemic trend, and that gap continues to grow.

This is a serious problem that is exacerbating China’s longstanding imbalances, but consumer spending is a relatively small share of Chinese domestic demand. Historically, investment in housing, infrastructure, factories, and other fixed assets helped offset chronic consumption weakness, limiting how much the trade surplus could expand. But that is not happening now.