Evaluating the Russia Sanctions via the Balance of Payments

The goal is to restrict access to critical imports. Achieving this by boycotting or embargoing Russian exports was neither realistic nor necessary.

The latest data imply that the dollar value of Russian imports of manufactured goods has almost recovered to the September 2021-February 2022 monthly average—and may possibly have surpassed that average depending on how one interprets the unusual increase in exports from Europe and elsewhere to some of Russia’s (relatively) friendly neighbors.

Some have interpreted this as a sign that the allies’ sanctions strategy was misguided. In particular, they believe that the democracies could have done more to constrain Russia’s access to imports by boycotting Russian oil and gas and by preventing major insurers from covering Russian seaborne shipments. According to this line of thinking, Russia’s large current account surpluses from earlier in 2022 were “savings” by the Russian state and are now being used to pay for imports even as energy prices—particularly Russian energy export prices—fall.

These claims do not hold up to scrutiny.

While all societies would benefit from reducing their consumption of fossil fuels, especially those produced by odious regimes, Russia’s reliance on energy exports is overstated. More encouragingly, the 2022 surge in Russia’s current account surplus resembles a classic balance of payments crisis driven by capital flight more than anything else. Tellingly, the surplus is (unfortunately) collapsing as imports recover.

Energy Boycott Impracticalities

Russia’s export revenues by themselves are irrelevant. What matters is the ability to translate export earnings into imports, either immediately or in the future through purchases of foreign financial assets. The financial sanctions and the export controls put in place by the global alliance of democracies focused on breaking this transmission. Those measures may have been insufficient and therefore need to be tightened, but they were aimed at the right target. By contrast, any strategy that aims to hurt Russia by reducing Russian exports must account for the longstanding Russian imbalance between exports and imports.

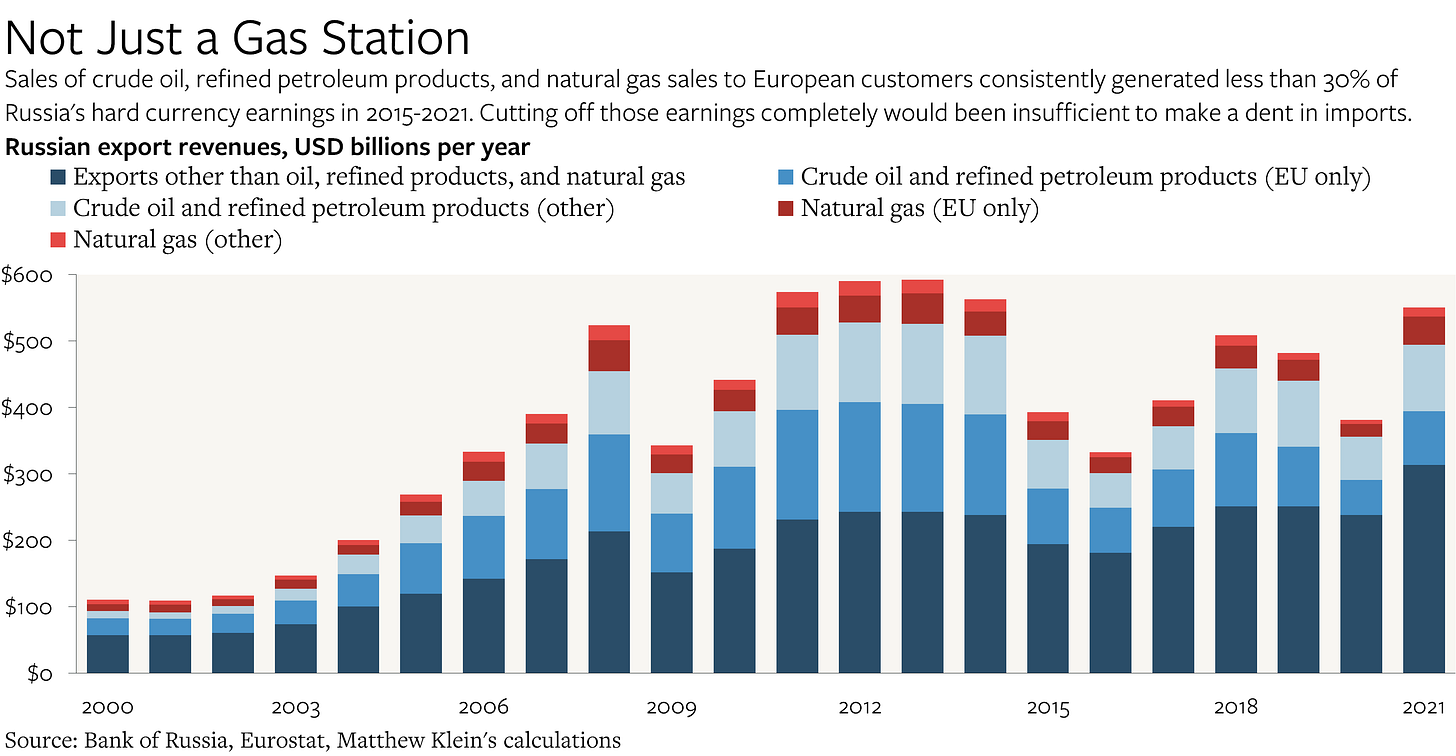

Ever since the 1998 crisis, Russian macro policy has been extremely conservative, with exports consisently exceeding imports.1 Moreover, the Russian economy adapted to the 2014-16 energy price crash with a sharp increase in non-energy exports, such as agricultural and other food products. As a result, Russian export earnings from goods and services other than oil, refined products, and natural gas were 5% higher in the second half 2021 on an annualized basis than total spending on imports in 2022.

Thus, even if a comprehensive energy embargo had been possible, it would not have been sufficient to meaningfully constrain Russian imports, because Russia’s non-energy export earnings alone would have been more than sufficient to cover the actual 2022 import bill. Other measures, such as the financial sanctions and export controls already in place, would still have been necessary. But if those other measures had been effective at limiting Russian access to critical components and military technologies, a binding energy embargo would have been superfluous. Europe acting alone would have had even less leverage, as I pointed out over the summer.

Suppose, however, that the allies had nevertheless managed to zero out Russian energy exports instantaneously.