The Overshoot's 2021 Year in Review

The big themes of the year, as well a roundup of what I've done since I launched in July

This is going to be my last note for a few weeks as I take some well-earned time off to be with family and recharge. To end the year, I will recap some of what I’ve been writing here since I started in early July. (It’s light on charts to avoid running into email length limits.) I’ve tried to organize my thoughts by geography and by theme. Many of you have subscribed within the past 6 weeks, for which I am grateful, and I hope that this will encourage you to go through the back catalog.

The Bumpy Boom: Growth and Inflation in 2021

The coronavirus has been the most important force in the world since the beginning of 2020, so it isn’t surprising that the production and distribution of ultra-effective vaccines in 2021 has been a boon for workers, businesses, and governments. This organic rebound was supported by the strength of household and corporate balance sheets across the world at the end of 2020—and then was turbocharged in January and in March by two additional U.S. income support packages that have so far boosted Americans’ personal income by $1.2 trillion. Extra spending in the U.S. also helped people in the rest of the world through additional imports.

But the virus is still around, with increasingly contagious mutations leading to surges in the summer (Delta) and now (Omicron). Moreover, the damage the virus wrought earlier in the pandemic continues to have lasting effects on our society.

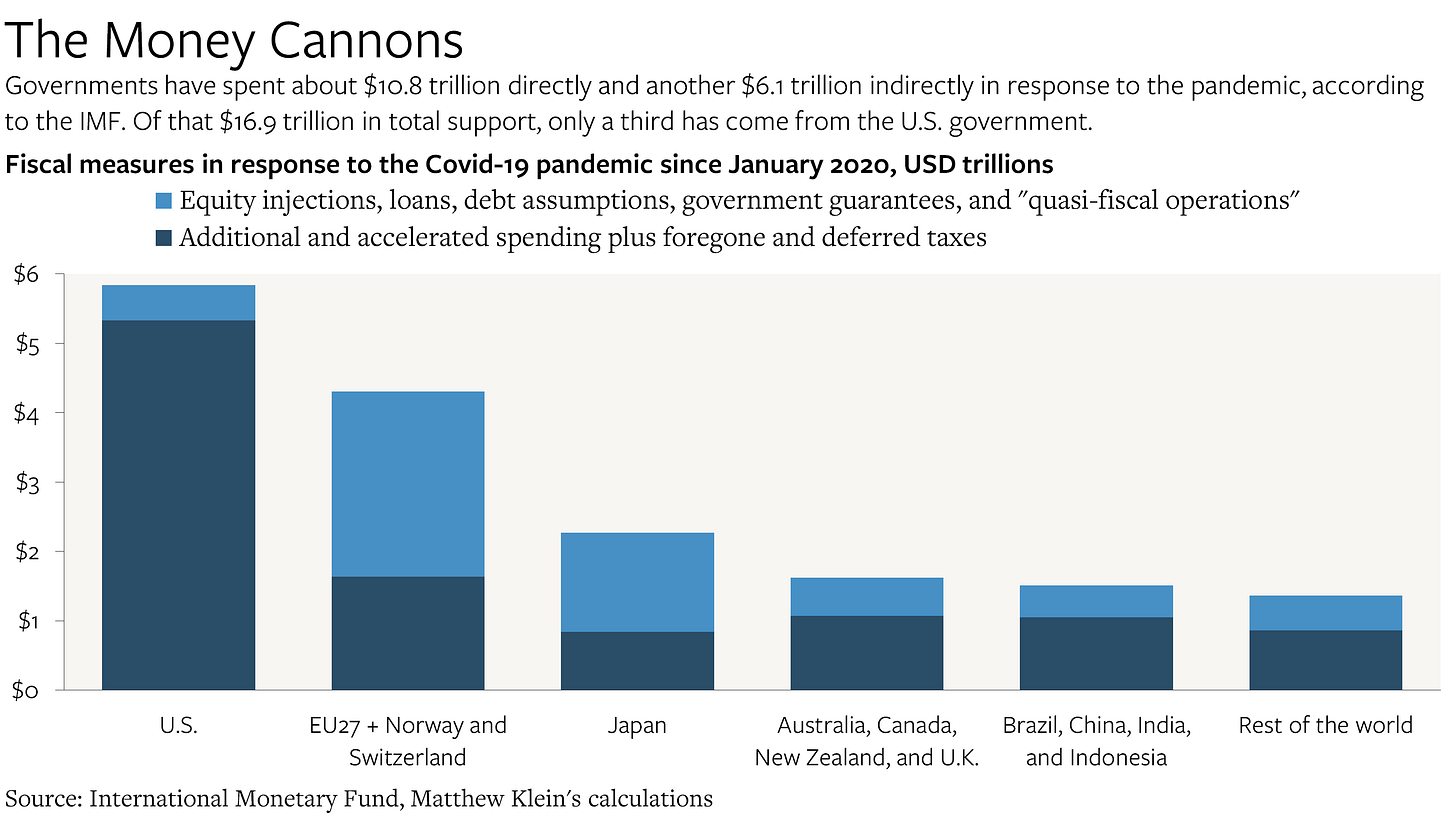

In the rich countries, the costs are mostly showing up in the form of inflation. Inflation is bad, but it’s surely better than what would have been the likeliest alternative: widespread job losses, business closures, bankruptcies, foreclosures, and evictions. Thankfully we didn’t choose that path. Instead, governments all over the world created and distributed unprecedented sums of money to prevent the unavoidable economic losses caused by the pandemic from turning into avoidable financial shortfalls.

The good news is that the price spikes seem to be one-offs associated with the disruptions caused by the virus and should therefore stop, if not reverse outright, once the pandemic is brought under control. Idiosyncratic problems in specific industries, most notably motor vehicle manufacturing and rental, oil and gas extraction, and meatpacking, have led to supply shortages that are pushing up the overall inflation rate.

There are two big risks for inflation going forward. If the pandemic never gets under control in any meaningful sense, then disruption will become “normal” and the costs associated with that disruption will become permanent features of our economic lives. Even if that doesn’t happen, we could be in serious trouble if consumers and businesses start to become concerned enough about the risk of future inflation that they change their behavior in economically destructive ways to hedge that risk, such as by hoarding commodities, spiriting money out of the country, or tightening financial conditions.

Below is a list of some of what I’ve written about these subjects since starting The Overshoot in July, mostly but not exclusively with a focus on the U.S.:

Inside America’s Household Savings Boom (July 12)

Takeaways from the GDP Revisions (July 30)

America’s “excess savings” are already getting spent because wages are lower (August 2)

What is Going on with the U.S. Job Market? (August 9)

America's Rebalancing Continues (plus a note on the nonfarm payroll benchmark revisions) (August 19)

The Smart Reason to be Worried About Inflation: a Conversation with Kevin Ferry (September 9)

Margins, Wages, Input Costs, and Inflation (September 17)

The Delta Jobs Slowdown? (October 8)

Inflation, Rents, and the Labor Market (October 13)

Paying the Covid Bill (October 19)

Growth Slowed in Q3 Because of the Chip Shortage and the Delta Variant. The Future Should Be Better. (October 28)

What's Happening With the U.S. Economy? (with Cardiff Garcia) (November 11)

The Case for Patience on Inflation (November 14)

U.S. Inflation Isn't Getting Worse (or Better). Keep Watching Motor Vehicles. (December 10)

Rational Exuberance vs. the Return of the “Old New Normal”: Longer-Term Expectations

American politics got off to a surprising start in 2021 when Democrats unexpectedly (and narrowly) won both of the Senate seats up for grabs in the Georgia run-offs on January 5.1 Moreover, they won by explicitly pledging to deliver additional income support payments to households. Until then, the big political risk was that the U.S. would be stuck with a divided government that wouldn’t be able to pass any meaningful legislation and instead be forced into unwarranted budget cuts—a re-run of 2011-2016 except in the middle of a pandemic.

The result was an upward jump in longer-term interest rates driven by faster expectations of real growth: rational exuberance. Between January 5 and March 18, the implied real yield on a 5-year note starting five years in the future rose by more than 1 percentage point even as the inflation outlook remained unchanged.

The Federal Reserve also responded by upgrading its growth forecasts for the years ahead. Starting in March 2021, officials concluded that the U.S. economy at the end of 2023 would be about 2-3% larger “under appropriate monetary policy” than would have been the case before the pandemic. The likeliest explanation: productivity gains in everything from retail to restaurants to remote working, likely due in part to the ongoing surge in entrepreneurship. Combined with newly optimistic assessments about the latent potential of the U.S. labor force, it’s not surprising why the Fed has been so willing to tolerate the prospect of a few years of excessive inflation to get to a better place.

But while the Fed has remained bullish, March turned out to be the peak of longer-term interest rates. The initial flurry of optimism leading up to the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act quickly dissipated once it became clear that it wouldn’t the first of a series of big pieces of legislation that would fundamentally change the trajectory of U.S. fiscal policy, much less the population structure or the distribution of income. The change in the outlook has coincided with a steady decline in forward yields to pre-Georgia levels, or about 1.2 percentage points below the 2017-2018 average. Traders seem to think that the “new normal” that emerged after the end of the financial crisis is where we’ll return in a few years.

More on all this in these notes:

Inequality, Interest Rates, Aging, and the Role of Central Banks (August 31)

The Federal Reserve Wonders What "Maximum Employment" Means (September 22)

What’s going on with interest rates? (Part 1) (November 9)

What’s going on with interest rates? (Part 2) (December 3)

The Pandemic's Impact on Business Dynamism in the U.S. and Europe (December 8)

What Should the Fed Do? (December 14)

The Fed Prepares to Raise Rates (December 15)

The Global Housing Surge

Homes tend to last for a long time once they’re built, most people buy them with borrowed money, and everyone wants one—contingent on location and size. Housing is therefore extremely sensitive to interest rates, to migration patterns, to changes in population size and structure, and to broader economic conditions.

The first year of the pandemic was a perfect constellation of factors to push up house prices all over the world. People wanted to move to get away from cities they thought posed higher risk of viral infection, and they moved to get more space because they were working from home and no longer appreciated urban amenities that were closed or put them at risk of disease. Central banks slashed interest rates to boost economic activity, which mechanically lifted house prices at a time when household credit was good and lenders had no reason to tighten standards. To top it all off, foreclosures and evictions were effectively banned even as disposable incomes boomed.

Different societies reacted in different ways, although waiting seems to have been the sensible approach as one-off shifts in behavior worked themselves out. The most extreme response was in New Zealand, which changed the law so that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand would start targeting house prices in addition to its other objectives. My writing mostly focused on the situation in the U.S. and in China (more on that lower down), but as far as I can tell the main issues apply across much of the world:

The Fed, MBS, and housing (July 6)

"Surge Pricing" is Over for U.S. Housing (July 26)

House Prices, Rents, and Inflation (August 17)

Europe Sets the Stage for Federalism—and Pro-Growth Policymaking

It was easy to miss while it was happening, but 2021 now looks like a year of serious change in many of the major European countries. The pieces are now in place for big shifts in economic policy in 2022, with Europe looking like the inverse of the U.S. as the center-left consolidates and plans to move forward on a range of initiatives. After many lean years for Europe’s social democrats, it looks like sustained fiscal expansion in the world’s second-largest economy is back on the menu.

The first to move was Italy. After the country’s governing coalition collapsed at the beginning of the year, President Sergio Matarella asked Mario Draghi—who had presumably been expecting to enjoy retirement after stepping down from the top job at the European Central Bank at the end of 2019—to become Prime Minister in February.

Since taking office, Draghi has spearheaded Italy’s application for €191.5 in EU recovery funds and he has signed a treaty with France to commit to closer cooperation.

But what really matters is what comes next for Draghi: the looming negotiations to modify Europe’s fiscal rules. For the first time in many years, the Italian government will be led by someone with enough gravitas and domestic support to avoid getting steamrolled. As I write this, Draghi and French President Emmanuel Macron have just published a column in the FT arguing for an overhaul of the rules to promote growth and investment. This is the key bit:

There is no doubt that we must bring down our levels of indebtedness. But we cannot expect to do this through higher taxes or unsustainable cuts in social spending, nor can we choke off growth through unviable fiscal adjustment…Just as the rules could not be allowed to stand in the way of our response to the pandemic, so they should not prevent us from making all necessary investments…We need to have more room for manoeuvre and enough key spending for the future and to ensure our sovereignty. Debt raised to finance such investments, which undeniably benefit the welfare of future generations and long-term growth, should be favoured by the fiscal rules, given that public spending of this sort actually contributes to debt sustainability over the long run.

Even more importantly, the French and Italians (and Spanish and Portuguese) can now expect support from Germany and the Netherlands.

Germany is the single-largest country in Europe, and its influence had long been amplified by the strength of former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s domestic standing. At the beginning of the year, it seemed likely that Germany’s Christian Democrats (CDU) would continue to lead the governing coalition, although they would probably have replaced the Social Democrats (SPD) with the Greens as their junior partner.

But then the CDU imploded thanks to the singular unpopularity of Armin Laschet, which in turn created an opening for the SPD and Greens. At the election in September, the two center-left parties won enough seats to form a government after striking a deal with the Free Democrats (FDP).

Crucially, while the FDP campaigned as defenders of the country’s “debt brake” and champions of fiscal rectitude, they had repeatedly hinted that they would be willing to get around Germany’s constitutional limits on borrowing with financial engineering. That’s why I was optimistic even before the election that the so-called “traffic light” coalition would be a boon for the global economy relative to the status quo. As it happens, the official coalition agreement closely matches what I had anticipated. (Be sure to also read my primer from the summer on how the German government could get around the debt brake.)

The German election was the most important development in European politics in 2021, but it wasn’t unique. The Dutch election back in mid-March has also turned out to be significant, although I confess that this wasn’t obvious at the time to most people, including me. And it’s still easy to miss what happened: after nine months of haggling over the results, the same four parties that constituted the previous ruling coalition have agreed to another coalition led by the same Prime Minister. (It was the longest-ever coalition negotiation in Dutch history.)

Yet the new Dutch coalition has just committed to a surge in social spending and climate-friendly investment, while disregarding Europe’s debt and deficit limits. The FT characterizes the deal as “a clear reversal” of the Dutch government’s longstanding tightfistedness. That’s attributable to the strong performance of the eurofederalist D66 party, which gained seats at the expense of the other coalition partners. They also have a good chance to take control of the Finance Ministry, which would potentially remove a major obstacle to greater Europe-wide fiscal support.

Put it all together and the pieces are in place for 2022 to be a big year for European reforms that should improve the continent’s long-term growth prospects.

China Considers “Common Prosperity”

China has had virtually the exact opposite experience of the U.S. since the pandemic began, both in terms of the virus itself and in terms of the economic response. Instead of supporting consumers, the government was stingy, forcing tens of millions of migrant workers from the city home to the countryside to live as subsistence farmers. Household spending remains far below the pre-pandemic trend, unlike in the U.S. or even in Europe. But Chinese manufacturers and real estate developers prospered thanks to strong foreign demand and thanks to explicit and implicit government support through the state-controlled banking system.

China’s policy mix was consistent with its pre-existing social arrangements and its pre-existing economic imbalances—imbalances that China’s top leaders have publicly warned about since the mid-2000s.2 The interesting question is whether 2021 marks a bit of a turning point. I think it’s still too early to tell, but the recent rhetoric and policies associated with Xi Jinping’s goal of “common prosperity” could mark a constructive shift. Alternatively, it’s simply a smokescreen for the government to crush any independent sources of economic power, while also potentially pushing the housing market into a severe downturn (maybe by accident).

Here’s what I’ve written on the subject for The Overshoot in 2021:

Understanding China’s Latest RRR Cut (July 15)

What is Going On in China? (September 2)

Appeasing the Chinese Government "For the Climate" Makes No Sense (October 21)

China’s Faltering Recovery? (November 19)

China’s Credit Tightening and Financial Outflows (November 20)

Odds and ends

Not everything I do fits neatly into the above categories. Below is a selection of some of my favorite pieces on subjects ranging from bank regulation to the Olympics to the balance of payments to pre-WWI Russian history:

Bank Regs Are Excess Profit Taxes (July 20)

Hosting the Olympics as an Economic Development Strategy (August 5)

Pro-Growth Isn't Anti-Environment (August 20)

Who Is Financing the Federal Government? (October 1)

Fumio Kishida's "New Japanese Capitalism" Might Be Just What the Country Needs (October 8)

Kornai, Keynes, the Coronavirus, and Kant (November 3)

Russia's Industrialization and WWI (December 22)

The "Banker to the World" is Back (December 23)

Finally, I should note that there are some interesting and important stories I haven’t—yet—covered here. Here’s a brief preview of what I want to look at more closely in 2022.

On top of the list: the revenge of the (EM) bond vigilantes. The governments of Turkey and Brazil both reacted aggressively to offset the economic costs of the pandemic. That worked well in 2020, but in 2021 it’s come at the cost of either a collapsing currency (in Turkey, although there has been an intriguing rebound recently with the introduction of dollar-indexed lira deposits) or surging interest rates (in Brazil). I did deep dives into both of those countries in 2018 when they were last experiencing acute periods of crisis. Time for another look!

2021 has also been a year of extraordinary shenanigans in the financial markets, from the meme stocks to SPACs to NFTs. I can’t justify spending too much of my time writing about all that when Matt Levine already provides top-tier coverage for free. That said, I have been pestering both American and international statistical agencies on how they treat cryptocurrencies and related products in the national accounts, the sectoral financial accounts, and the balance of payments, and I plan on writing on the subject once I hear from more of them. (I’ve already heard back from the Fed but not anyone else—yet.)

Anyhow, here’s to hopefully staying healthy and to having a happy new year! I’ll see you in 2022.

Future historians may determine that the violent assault of the U.S. Capitol the following day was the most important event in U.S. politics in 2021. However, it doesn’t have any obvious link to economic or financial outcomes, so I will refrain from discussing it here.

If you want to learn more about this, please read Trade Wars Are Class Wars.