The Overshoot's 2022 Year in Review

From puzzles in U.S. GDP data to the global impact of Russia's war on Ukraine, a look back on the past year and some thoughts on what might lie ahead.

I was interviewed by the Harvard Business Review about the economic outlook for 2023. I also recently had the chance to chat with Michael Gayed of Lead-Lag Live about Trade Wars Are Class Wars and the situation today.

This was supposed to be the year that we returned to normal.

In some ways, we did: the excesses of the SPACs, meme stocks, cryptoassets, money-incinerating tech startups, and housing markets were largely purged by the end of 2022. More subjectively, politics and culture also seem saner now than they have in years, at least in the U.S.

But compared to what many of us were expecting (and hoping for) 12 months ago, 2022 was a year of tumult that was anything but normal. What follows is a selection of some of the pieces I have written this year, organized by geography and theme. You can find the full list of everything I have done since starting The Overshoot in July 2021 in the archive, which I would encourage you to explore when you have the chance, especially if you only subscribed recently.

The Russian War on Ukraine

Putin’s invasion has killed hundreds of thousands, displaced millions, and created choas in world markets for food, energy, and industrial commodities. Russia has been transformed into a pariah state suffering from an exodus of talent and capital, while Ukraine is now a serious contender for membership in the European Union—and in need of at least $1 trillion in reconstruction aid. The world has changed in ways we are only beginning to understand, from the surge in the Japanese defense budget to the global rise in food insecurity. (I strongly recommend reading Lawrence Freedman’s essays on the military situation and Yakov Feygin on Russia’s internal dynamics.)

I have looked at the Europeans’ reliance on Russian natural gas, the relative vulnerabilities of the Russian and allied financial systems, the impact of the war on global food supplies, the effects of the war on Russia, and the longer-term implications of the conflict for domestic political economic and international statecraft. Below is a selected list, in chronological order:

Russia Was Prepared to Withstand Sanctions. Why Wasn't Europe Prepared to Impose Them? (February 22, 2022)

Russia Was Already Cutting Off Europe's Gas Before Invading Ukraine. What Can Be Done? (February 24, 2022)

Mapping Banks’ Russian and Ukrainian Exposures (March 1, 2022)

The Implications of Unrestricted Financial Warfare (March 8, 2022)

Russia’s Attack on the World's Food Supply (March 15, 2022)

How to Dominate the Economic Battlefield with a “Freedom Fund” (March 24, 2022)

The Sanctions Are Already Working (April 21, 2022)

Russia Is Losing Access to Imports (May 16, 2022)

On the Russian Oil Sanctions (June 2, 2022)

The Squeeze on Russia Is Loosening (August 16, 2022)

The Sanctions’ Impact on Russia (August 19, 2022)

Russia’s Imports Are Surging. Does It Matter? (September 16, 2022)

Russia Sanctions, “Mobilization”, and Capital Flight (November 8, 2022)

From U.S. Reflation to…?

The U.S. economy boomed in 2021, with employment, incomes, and real consumer spending all rapidly returning to where they would have been in the absence of the pandemic. This exceptional economic performance coincided with an unwelcome increase in certain prices, but that was a relatively small price to pay for smoothing out the adjustment costs of the pandemic. Moreover, most of those price gains could be explained by specific production shortfalls or demand shifts attributable to the pandemic.

Things were different in 2022. The U.S. economy more or less stagnated even as inflation got worse. Yes, inflation as a whole topped out in the first half of 2022, and inflation should continue decelerating into 2023 as commodity price spikes fade and manufactured goods prices fall outright. But the underlying trends have been less encouraging.

The good news is that core nominal consumer spending power (mostly labor income) is still rising fast enough to keep pace with price increases and preserve the average American’s living standards without undermining most households’ balance sheets. The bad news is that core nominal consumer spending power (the average worker’s wage) is rising too fast to be consistent with the Federal Reserve’s inflation target—unless there is a massive change in the split between consumer spending and personal saving, which would have all sorts of implications for the rest of the economy.

For perspective, the latest data imply that underlying inflation has accelerated from around 2% a year to around 4-5% a year. This is not a crisis, and certainly not what people who who were hyperventilating about inflation earlier in 2022 were worried about when prices were rising at annualized rates of 10-12%. In fact, current trends are broadly consistent with what many economists had been calling for on the eve of the pandemic. Fed officials are less sanguine, however, which is why they have been trying to tighten financial conditions enough to get businesses to slash hiring and investment. A few highlights of my coverage:

Understanding Covid-flation (January 19, 2022)

The U.S. Job Market Is Hot* (February 2, 2022)

The Fed Is Still Waiting for Supply (March 16, 2022)

U.S. Inflation is Getting Worse (and Better?) (May 12, 2022)

What Should We Do About Inflation? (Part 1) (June 14, 2022)

The Federal Reserve Brings the Pain (June 16, 2022)

What Should We Do About Inflation? (Part 2) (June 22, 2022)

Most Americans Are Doing Well. For Now. (July 1, 2022)

Is America’s Job Market “Too Good”? (August 9, 2022)

The “Data-Dependent” Fed and the Data (September 20, 2022)

The Fed Tries to Get Out in Front (September 22, 2022)

Wages, Prices, and Taming U.S. Inflation (October 19, 2022)

Patience on Inflation Is Paying Off. Sort of. (November 17, 2022)

U.S. Inflation Reprieve? (December 14, 2022)

The Fed Is Getting Less Sanguine About Inflation. Here’s Why. (December 16, 2022)

Puzzles in the U.S. National Accounts

Before the most recent invasion of Ukraine, I was vexed by the “statistical discrepancy” between two theoretically equivalent measures of economic activity. It all started with what I thought would be a straightforward analysis of the financial and product accounts. Somehow I ended up falling into rabbit holes of missing investment spending and different ways of counting motor vehicle production. As of now, the official answer is mostly that the BEA had been overestimating wage and salary income (I still find that hard to believe) while underestimating consumer spending on pandemic-affected services. There was also an intriguing revision to estimates of how much companies distributed in dividends vs. retained earnings. Some of what I wrote, in chronological order:

Are America’s “Excess” Savings Here to Stay? (January 10, 2022)

Where Have the “Excess” Savings Gone? (January 12, 2022)

U.S. “Excess” Household Savings and the Balance of Payments (January 25, 2022)

What the New “New Vehicles” Price Index Tells Us (February 9, 2022)

How Worrying is the Q1 GDP Decline? (May 5, 2022)

U.S. Economic Data Aren’t Adding Up (May 27, 2022)

Is the 2022H1 GDP Decline...Fake? (July 31, 2022)

Solving One Puzzle in U.S. GDP Data (Maybe), Finding More (August 31, 2022)

The Covid Recovery Looks Different Now (September 30, 2022)

China’s Struggle With “Covid Zero”—and a Balance of Payments Puzzle

When one of the world’s largest economies ends up going in a completely different direction from everyone else because of its distinctive domestic policy choices, it’s important to pay attention.

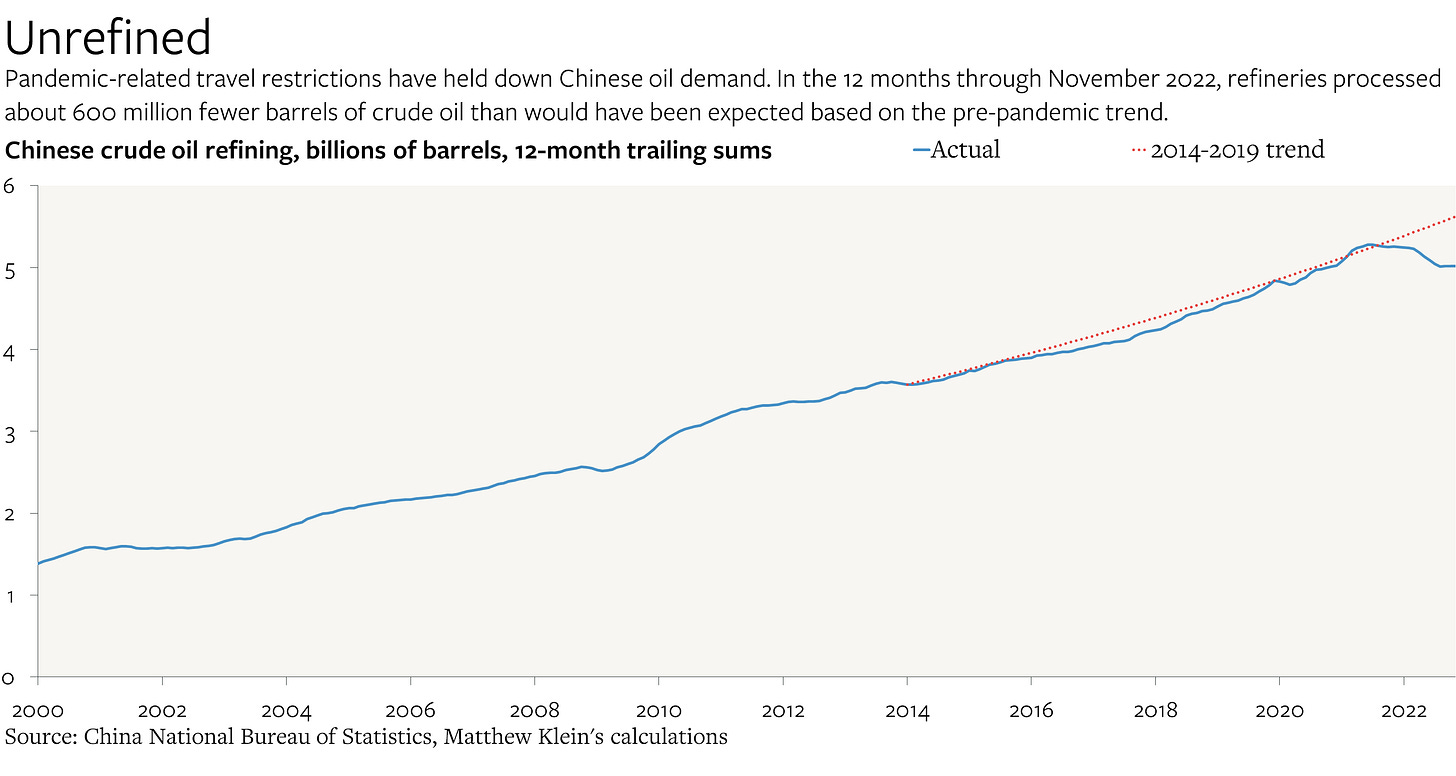

The Chinese government stood out in 2020 for refusing to help its consumers and workers during the economic downturn. In 2021, it began a severe crackdown on a range of private businesses in industries ranging from education to internet software to real estate development. Then in 2022 it imposed new draconian lockdowns in an attempt to suppress the more contagious covid variants, rather than relying on vaccines and other pharmaceutical treatments to manage the pandemic. Those measures proved so unpopular that they led to the biggest nationwide protests since 1989—and a complete reversal of the policy that has led to massive outbreaks that seem to be overwhelming the strained healthcare system.

China’s internal troubles could upend the global supply of manufactured goods, but so far the main impact has been a sharp drop in domestic demand reflected in lower spending on imports and lower prices for commodities. Beyond the impact on the lives of 1.4 billion Chinese, the sudden switch from “covid zero” to “herd immunity” could have profound consequences for global balances between production and consumption, especially if the population is able to achieve some form of post-pandemic normalcy.

Meanwhile, a weird discrepancy has emerged between China’s trade surplus in physical goods according to customs data (about $1.33 trillion from January 2021-September 2022) vs. the official balance of payments numbers for the same period ($1.08 trillion in 2021Q1-2022Q3). This is not the only puzzle in the country’s balance of payments, but it is the most glaring one. One possibility is that the State Administration of Foreign Exchange has been massaging the data to hide evidence of capital flight by residents seeking to escape covid-related restrictions and the policy-induced housing bust.

Last Looks at the Pre-War World (2): China Bounces Off the Lows? (March 25, 2022)

“Covid Zero” is Crushing China (May 20)

Some Chinese Balance of Payments Puzzles (October 13)

Japan’s Singular Quest for More Inflation

Unlike policymakers in the rest of the world, Japanese officials hope that recent price spikes will translate into durable changes in consumer and corporate behavior. After three decades of nominal income stagnation, they believe they have been presented with a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reset Japan’s inflation baseline from 0% to 2% a year.

Understandably, this unusual position has done all sorts of interesting things to Japan’s currency, bond market, and other asset prices. It has also led to a lot of confusion about what Japanese officials want, especially recently. My attempts to cut through the noise:

Looking at Japan with FT Unhedged (October 2, 2022)

The Japanese Government Is Right to Defend the Yen (Part 1) (October 27, 2022)

The Japanese Government Is Right to Defend the Yen (Part 2) (November 1, 2022)

The Bank of Japan Makes a Tweak (December 21, 2022)

Odds and Ends

Much of what I wrote this year falls into these few categories. A pieces did not, however, including two book reviews and my gradual ongoing attempt to update the narrative of Trade Wars Are Class Wars in light of current events:

Thoughts on DISORDER by Helen Thompson (May 10, 2022)

“Quantitative Tightening” So Far (July 12, 2022)

Trade Wars Are Class Wars, 32 Months Later (Part 1) (September 7, 2022)

Trade Wars Are Class Wars, 34 Months Later (Part 2) (November 21, 2022)

“Slouching Towards Utopia” and “The Long 20th Century” (November 29, 2022)

The “Tech Wreck” and Ireland (December 10, 2022)

Anyhow, here’s to the end of 2022 and to a healthy and happy 2023! Thank you again for subscribing to The Overshoot. See you in the new year.