The Overshoot's 2023 Year In Review

Looking back at some of the big themes of the past 12 months.

Normalcy may have returned, but the world of 2019 is gone. We are starting to find out what comes next.

With China abandoning “Covid Zero” restrictions at the end of 2022 and the newest variants proving to be (mostly) harmless, especially against vaccines, 2023 was the year when we finally put the pandemic behind us.1 But the virus and the associated policy responses have had a lasting impact on society—and, by extension, on the economy and financial markets. Moreover, while the price shocks attributable to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have faded, the ensuing momentum for rearmament and industrial policy have not.

What follows is an attempt to synthesize what I found most interesting in 2023, with references to a few of my favorite pieces from this year.

You can find the full list of everything I have done since starting The Overshoot in July 2021 in the archive, which I would encourage you to explore when you have the chance, especially if you only subscribed recently. If you are not sure where to start, I would recommend reading my retrospective on The Overshoot’s first two years, which I published back in July. Thank you again for subscribing!

The Global Implications of China’s Missing Recovery

The biggest question at the end of 2022 was what would happen after China’s “Covid Zero” restrictions ended. Weak Chinese demand had muted the impact of Russian supply disruptions, particularly in oil and natural gas, and therefore contributed to disinflation in the rest of the world. Would that change once Chinese were allowed to leave their homes again?

It turns out that the answer has mostly been “no”.

Crude oil refining was up sharply from last year in much of 2023 but fell sharply in November and remains well below trend.

Chinese consumer spending has grown just 3% a year on average—including inflation!—since 2019. Consumption is about 14% below where it would have been if spending had grown in line with the pre-pandemic trend.

Meanwhile, the housing bust that began in mid-2021 has continued to be a drag on overall economic activity and Chinese demand for industrial commodities, although the full impact has yet to be felt.

The predictable response has been a surge in Chinese exports relative to imports, alongside an apparent uptick in capital flight. This has generated panic in Europe, but much less of a reaction in the U.S., which seems to have mostly insulated itself.

Whither Globalization? And What Would that Even Mean, Anyway? (February 7, 2023)

China's Missing Post-Pandemic Rebound (July 18, 2023)

Is the Chinese Government Pushing Down the Yuan? (July 25, 2023)

China Is Now Growing Slower Than the U.S. (August 16, 2023)

Danish Weight Loss Drugs vs. Chinese Cars: Two Models of Export Booms (September 12, 2023)

The Threat from China's Capital Flight (November 10, 2023)

Managing Economic and Financial Entanglements With China (November 20, 2023)

Michael Pettis and I also covered this question in several episodes of our UN/BALANCED podcast, which I encourage you to check out if you haven’t already.

Decomposing America’s Disinflation

Inflation has slowed sharply since the first half of 2022. In fact, headline inflation in 2022H2 was already much slower than in 2021H2-2022H1 thanks to energy prices, while there has been almost no additional headline disinflation in 2023.2 The disinflation since June 2022 should not have been a surprise. The question is what it means for prices and interest rates going forward.

The disruptions of the pandemic and Russia’s war were always going to impose an economic cost, and policymakers rightly chose to absorb that cost with a one-time surge in prices, rather than debt defaults and asset writedowns. Those exceptional price increases would stop as businesses and consumers adapted to the disruptions.

The big question was always whether this adjustment process would take so long that it changed behaviors and transformed temporary disruptions into persistently faster underlying inflation. In other words, after the dust eventually settled, would inflation revert to its pre-pandemic norm, or would it do something else?

Answering this question is hard, because the one-offs have been so large and because the underlying trend cannot be observed until long after the fact.

I have relied on two complementary methods.

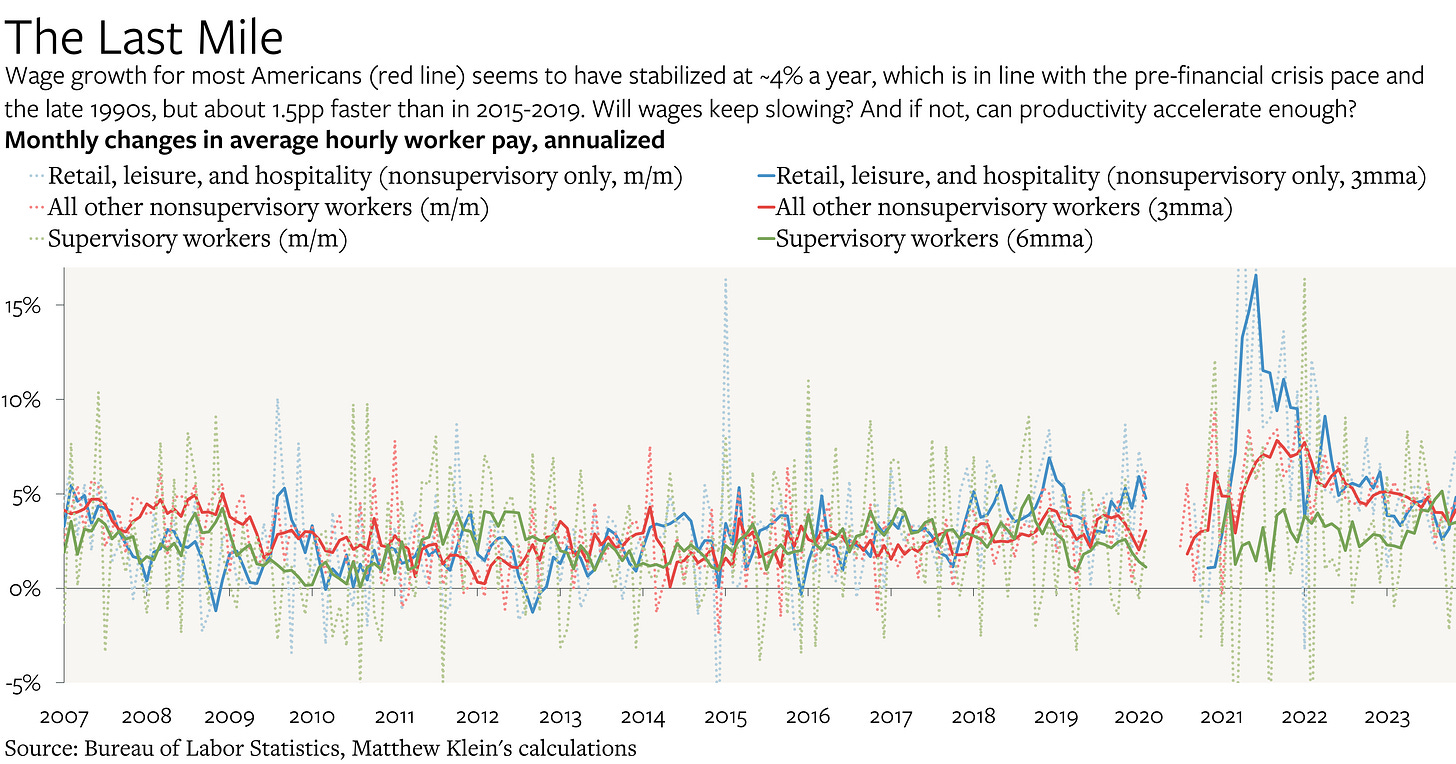

First, I have been tracking trends in workers’ wages. Rising worker pay does not cause inflation, but most consumer spending is financed out of wages—and most people tend to spend whatever extra money they earn on goods and services. If pay rises in line with businesses’ ability to produce, then the extra spending translates entirely into additional gadgets, movie nights, and other forms of real consumption. If pay rises faster than production and that extra pay is spent, businesses will have to find a way to ration supply, and the most straightforward approach is to raise prices.

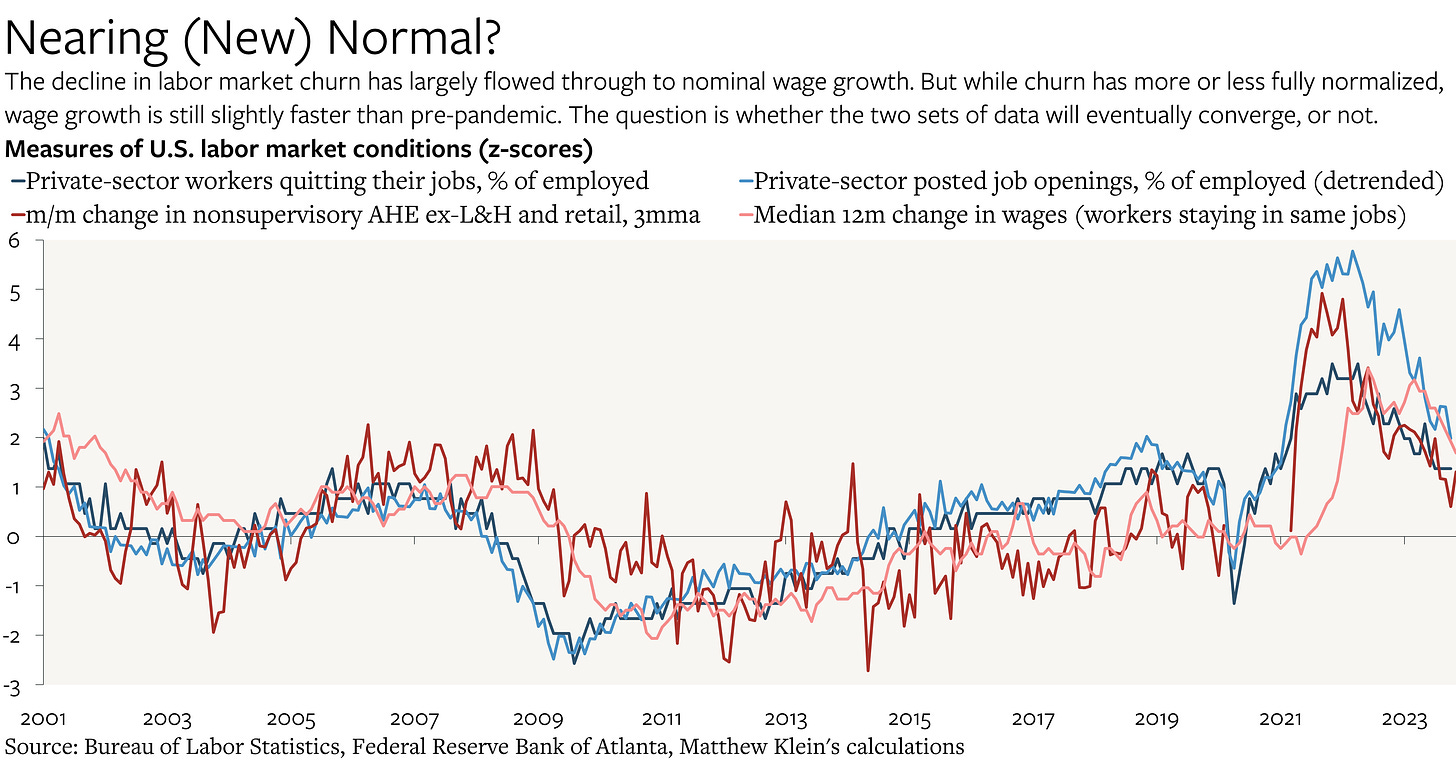

Productivity seems to be rising in line with longer-term norms. But average worker pay is still rising a bit faster than before, even if churn in the job market has mostly ended.

My other approach to estimating underlying inflation has been to construct price indices that strip out components that might be affected by idiosyncratic factors, in the hope that whatever remains is the best indicator of where inflation will end up after the dust settles. Federal Reserve officials suggested looking at services excluding energy and housing. I prefer a slightly different version that also excludes “imputed” prices for services with no market prices, such as gambling and “free” checking accounts.

Similar to measures of hourly wages, this seemed to have accelerated by about 2 percentage points compared to pre-pandemic. Unlike broader measures of inflation that were sensitive to the prices of energy and manufactured goods, this index had not been showing any signs of slowing—until this summer. But it has since been re-accelerating (red dashed line).

I have written a lot on this subject, but these are my favorite pieces from the past year:

Reconsidering the "2020s as 1940s" Analogy (March 8, 2023)

"Greedflation" and the Profits Equation (June 10, 2023)

The Unresolved Tension Between Prices and Incomes (August 14, 2023)

Is the Fed Peaking Too Soon? (November 2, 2023)

The Fed Prepares for Rate Cuts. But Why? (December 14, 2023)

The Missing Policy Tightening—Or Rising Neutral Rate?

One of the funny things that happened in 2023 was that policymakers kept saying that they were being “restrictive” despite all of the data pointing in the other direction. Yes, bank lending slowed, and a few banks blew up in the dumbest possible ways, but real activity accelerated this year while risk asset prices ripped up. I cannot claim to know why exactly this happened, but the simplest explanation is that policy was not actually as tight as advertised (at least relative to what the economy needed).

For one thing, debt has simply not been that important at financing growth throughout the post-pandemic recovery, which naturally limits the impact of higher interest rates on actual spending. Similarly, consumers and businesses have much healthier balance sheets than they did in 2019, with more cash on hand, more assets, and less debt. That should raise the set of “equilibrium” interest rates relative to a world where the private sector is heavily constrained by existing obligations.

It also worth noting that while the Fed has been shedding assets at a brisk clip, the corresponding reduction in the Fed’s liabilities can be attributed entirely to its overnight reverse repo facility, which was effectively like a high-yielding checking account for money market funds. Those money funds simply rotated into U.S. Treasury bills and shorter-term notes. In fact, reserves held by banks have grown by about $500 billion since the end of last year.

One thing that did not happen was a hidden fiscal stimulus. While the budget deficit has widened a lot in 2023 relative to 2022, this seems to be a function of higher interest rates and lower capital gains tax receipts (which are based on gains/losses from 2022).

One interesting possibility is that the Treasury’s (relative lack of) debt issuance and its preference for borrowing via bills may have depressed interest rates and risk premiums relative to what they otherwise would have been. “Households and nonprofits”, which includes hedge funds, foundations, endowments, and family offices, have been by far the biggest buyers of marketable U.S. Treasury securities recently, along with money market funds.

With interest rates plunging over the last few weeks, the natural question is whether policymakers may have inadvertantly eased more than would be appropriate given the strength in the economy. A few pieces I have written on these themes:

"Quantitative Tightening" and the U.S. Banking System (February 15, 2023)

Thoughts on the Bank Bailouts (March 13, 2023)

Banks Are Blowing Up While the Economy is Strong. Time to Worry? (May 10, 2023)

Who Has Been Buying U.S. Treasury Debt? (June 24, 2023)

What Has Policy Tightening Accomplished So Far? (July 14, 2023)

There Is No "Stealth Fiscal Stimulus" (August 2, 2023)

The NY Fed Trading Desk's Time to Shine? (September 1, 2023)

Global Questions (and Odds and Ends)

The rest of my coverage this year covered a range of subjects, often with an international angle, although sometimes focused on nuances of U.S. economic statistics. These are a few of my favorites:

Some Thoughts on U.S. International Economic Statecraft (January 18, 2023)

The Bank of England's Jonathan Haskel on Inflation, Productivity, Brexit, and More (February 13, 2023)

The Case of the Missing Planes (May 18, 2023)

An American Investment Boom Would Be Good for the World (June 13, 2023)

Financial Fragmentation (June 27, 2023)

Europe's Imbalances in Pandemic and War (August 11, 2023)

Less Tax Evasion, a Profit Boom, and a Persistent Interest Puzzle: Highlights of the 2023 Comprehensive NIPA Revisions (Part 1) (September 29, 2023)

"Excess" Savings Are Higher Now (Sort Of): More Highlights from the 2023 Comprehensive NIPA Revisions (October 4, 2023)

The Russia Sanctions Need a Reset (October 11, 2023)

Tracking Russia's Financial Outflows, Again (October 16, 2023)

Argentina and the Limits of Fiscal Space (December 11, 2023)

Thanks again for reading and subscribing! See you in 2024.

My former colleague John Authers has an excellent piece showing how this could have been expressed in a hypothetical long-short equity portfolio.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 9% from June 2021 to June 2022, and then was flat between June 2022 and December 2022. CPI inflation from December 2022 through November 2023 has been 3.8% annualized. The Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) price index rose 7% between June 2021 and June 2022, rose at a yearly rate of 3.2% from June 2022 through December 2022, and has grown at a yearly rate of 2.7% from December 2022 through November 2023.

Wonderful coverage this year Matt!

Great work as usual! Question for you: it looks like changes to PCE have outpaced both earnings and DPI . . . does that mean that PCE should come down soon enough, or that wages will catch up, or something else entirely? https://www.therandomwalk.co/p/consumption-has-grown-more-than-income